Some background on Stay Close

It was in January 2013 – when relations between Iran and the UK were particularly strained and there seemed little hope of reconciliation – that I first had the idea for Stay Close.

As a British-Iranian living in London, I experienced the souring political relations between my two countries as a very personal tension slowly weighing me down. The situation made me feel dually powerless and compromised: resigned to half-heartedly defending Iranian and British positions in different areas of my life and increasingly struggling to reconcile the opposing factions within my own identity.

Against this backdrop I established Stay Close, a music project encouraging collaboration, exchange and understanding between the UK and Iran. The project has stretched over 10 months, included research periods in London and Tehran, involved over 80 participants and resulted in a new five movement piece entitled Only Sound Remains combining elements of Iranian and Western musical styles as well as musicians from both traditions.

An interesting feature of Iranian classical music is that the melody types on which the tradition is based are all notated within a singular volume called the radif. This makes it particularly accessible to composers from other musical traditions and thus I was able to use short melodic fragments from Iranian music as the basis for theme and variation amongst both Iranian and Western musicians. Two specific melody types were particularly important in the 5th movement of Only Sound Remains, namely Jamedaran and Reng-e Farah, both in the mode of Homayoun.

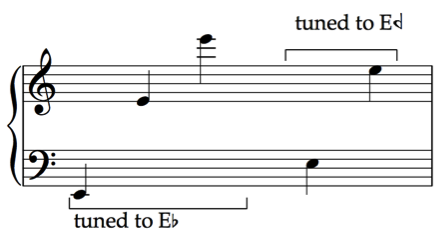

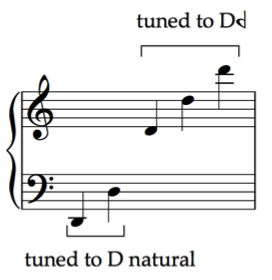

It is Iranian modes – or dastgah – that provide the tonal basis of the piece such that the five-movement work moves from the dastgah of Homayoun to Segah and back to Homayoun again. The tonalities of these modes are notated below.

A real challenge of using dastgah was asking Western musicians to master the playing of unfamiliar microtones within a relatively short space of time. In the case of the harp, particular complications arose due to the fact that the piece required both microtones and natural notes to be played on the same strings with no time for retuning. After many false starts – and wrong notes – I finally devised a tuning system that allowed this instrument to move between the various tunings required of the ensemble.

Only Sound Remains also employs typically Iranian rhythmic cycles which I was fortunate enough to learn about through many hours of speaking with tombak player of the ensemble, Fariborz Kiannejad. These are particularly evident in the 3rd movement of Only Sound Remains which makes use of a rhythmic cycle in 13, and in the 4th movement which is an improvised tombak solo moving through a wide variety of rhythmic cycles.

Alongside my efforts to make use of aspects of Iranian music in the piece, my own background as a Western classical composer is indelibly marked on the work. The instrumentation is the most obvious example of this with an ensemble including five Middle Eastern musicians playing ney, voice, tombak, tar and kamanche – instruments I had never written for – and the more familiar flute, clarinet, trombone, harp, violin, viola, cello and double bass. Moreover, while Iranian music is particularly characterized by unison or homophonic textures – particularly solo and accompaniment – the 1st movement of Only Sound Remains makes use of pointillist techniques that encourage musicians to consider their position in the ensemble beyond that of either soloist or accompaniment.

The end result is a very personal piece that attempts to connect and reconcile my Iranian and British identities within a new musical work. For any more information on the processes of Iranian classical music see here for an article by me and please come along to the final (free) performance which will take place at City University Performance Space on 20th May 2014.